“I’ve got strong convictions about the way that I live/ I’ve got no concessions that I’m willing to give” — Petra

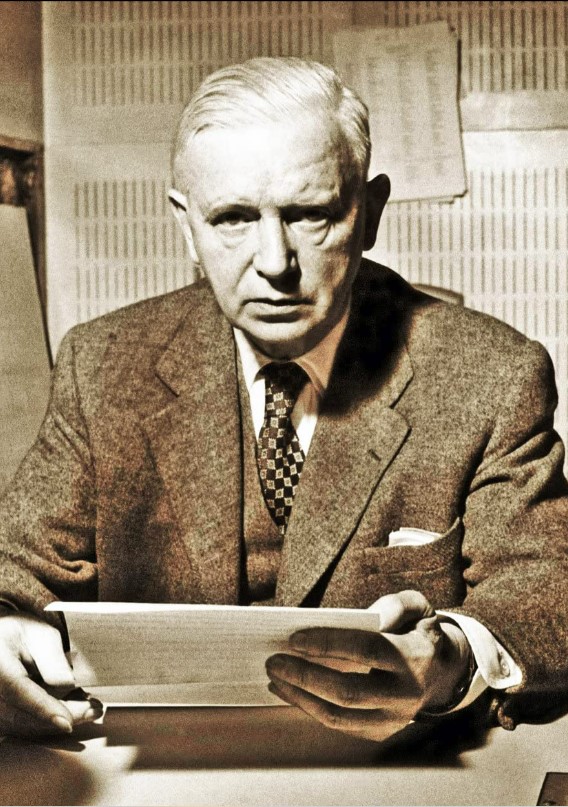

In some way, all the protagonists in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s films embody this notion: being so powerfully swayed by a set of ideas that they are willing to endure personal physical and psychological harm as a way of demonstrating not only their own faith but also the compulsory elements of these sets of ideas. Beginning his career with the silent film The President in 1919, for the next decade Dreyer would explore notions of deeply-held faith and the manners in which it effects both the holder and those they encounter. As a consequence, also, of the nature of the industry at the time, Dreyer was restricted largely to producing his unique projects in Scandinavia and Germany, perhaps due to the aftermath of World War I in which a vacuum developed that left many feeling isolated and in search of more profound meaning than that which resulted in catastrophic wartime. However, as a filmmaker and artist, it is widely acknowledged that Dreyer’s style and thematic focus crystalized beginning in 1928 when he released his first French production: The Passion of Joan of Arc. Therefore, this analysis of Dreyer will center around his last five features which became more sophisticated and complex as well as more emblematic of what Paul Schrader called the transcendental style: a powerful combination of faith, asceticism and search for spiritual idealism through the language of cinema.

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

In an essay he wrote about the movie, Dreyer states his purpose in adapting this story: “I wanted to interpret a hymn to the triumph of soul over life,” and there is perhaps no other historical character who embodies this idea as much as Joan of Arc, whose legacy is centered on her ability to find a transcendent meaning that gave her purpose as well as embolden others to follow her and the goal she embraced. More than simple nationalistic independence, Joan gave her fellow Frenchmen courage and responsibility to uphold and maintain the ideal state for which they strived. In doing so, she transcended her class, gender and age and became a symbol of loyalty and purity for all of France.

To realize the story of Joan of Arc, Dreyer pored over the numerous documents and transcripts depicting the encounters between the judges and this most remarkable of young women. He also forbade the actors from wearing makeup and allowed the sets to be designed without his input. As Dreyer said, “What counted was getting the spectator absorbed in the past.” The result is a movie experience not easily forgotten, largely due to Dreyer’s unique filmmaking style. With sharp camera angles and extreme close-ups seldom used at this point in cinema, The Passion foretells the style of directors like Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson, who also explored ideas of spirituality and moral responsibility in idiosyncratic forms. These themes are further realized through the astonishing performance of Renée Jeanne Falconetti, a thirty-five-year-old stage actress with one film credit to her name prior to Dreyer seeing her in a stage production and casting her as Joan. In the same essay Dreyer noted that by casting Falconetti he found “the martyr’s reincarnation,” which illustrates just how significant her contributions to the production are. With her large, expressive eyes, sharp nose and wide lips, the face of Joan becomes as much a character as her soul and as a result, Falconetti is able to craft a mesmerizing performance with the smallest facial movements, which Dreyer captures with great clarity.

The structure of the story is simple enough, but the psychological weight of what is at stake puts a tremendous amount of pressure on Joan and the audience as she defends not her actions but her faith. The pain in her face becomes more visible as the trial progresses but the rigidity of her belief is what sustains her through this barrage of questions and accusations. To visualize this, Dreyer shoots most of the trial on a tilted angle until Joan recants her confession of sin against the church. At this point, the camera straightens out and we see that Joan has become ‘right’ with God. The result of this is death but members of the crowd realize her innocence and as she dies Dreyer gives close attention to the smoke rising above her body and into the heavens. Thus, Joan’s soul is reunited with God and her status as a saint and ‘the heart of France’ is secured.

Vampyr (1932)

After facing a lawsuit regarding a contractual dispute with his previous film’s production company, Dreyer went the independent route in securing funding for his next project via the wealthy socialite Nicolas de Gunzburg, who simply asked for the lead role in return for footing the bill. Given Dreyer’s proclivity to work primarily with non-professional actors, including most of the cast of this production, this decision did not impact his artistry. The story idea, however, stemmed from Dreyer’s study of various supernatural occurrences in Europe as well as the enormous success of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which had recently been adapted for the stage. The result is one of the more intriguing submissions in the director’s output: Vampyr, Dreyer’s first introduction to sound, although much of the story is told through title cards and the sound was recorded post-production due to his unfamiliarity with the technology at this point. Yet visually, Dreyer’s style remains as striking and memorable as before through his use of soft focus and quiet tension to create a mood of sinister forces lurking about at every turn.

Like Joan of Arc, Dreyer saw numerous opportunities in this tale to explore spiritual and mythical themes as well as utilize the newly created sound technology. Based on a collection of stories by Irish gothic author J. Sheridan Le Fanu, the decision to use less dialogue and more visual narration is useful in terms of creating a sense of mystery and uncertainty. Despite the lack of quality audio recording and dubbing issues, Dreyer plays down these elements and emphasizes the tone of dread and terror, as well as themes of the origin of evil and its ability to spread amongst a small community. Like his previous work, Dreyer’s camera is slow and meditative, concerned with establishing the spiritual impact of entering a place that challenges one’s faith and soul. The smooth movements of the tracking shots entice the viewer, and a sense of fear grows along with questions regarding the nature and origins of this evil and what its objectives might be.

For the protagonist, Allan Gray (played by Gunzburg but credited as ‘Julian West’), his wide-eyed curiosity stems from a fascination with the supernatural, which of course remains a deep-seeded human longing. Indeed, like so much of Dreyer’s work, Vampyr attempts to understand the profundity of the unexplainable. Unlike the innocence and purity of Joan of Arc, however, the focus here is on the quiet malevolence and possession of vampires. Yet, these are not vampires as understood in the modern sense or even by Stoker. Here the mood is heavier, and the tone is quite serious, focusing on the malevolent elements of vampire mythology. Regardless of the ideas most people have about vampires, in Dreyer’s hands they are seen as demons, capable of possessing a person and forcing them into submission. Persistence, faithfulness and awareness are needed but it will also take strong belief in divine intervention to defeat this dark power. The lack of compelling special effects and action sequences forces audiences to walk through a deliberate narrative maze that is challenging while also serving to emphasize the notion of a dream-like state that prevents one from behaving to their full potential. In such a state of mind, is it possible to overcome this curse of possession?

In his biography of the director, writer Maurice Drouzy connects the casting of an elderly woman as the vampire (in the original story she was a young seductress) to the figure of Dreyer’s adoptive mother while Léone, the young woman possessed, represents Dreyer’s birth mother. This, as essayist Mark Le Fanu points out, is indicative of the number of various names given to the main characters in the story wherein each seems to symbolize the two sides of the human spirit and furthers the idea that, in some way, these demonic vampires might be humans at the core who have somehow gone astray. This idea is most prevalent in an extended dream sequence when Gunzburg imagines seeing himself dead in a coffin and being buried by the vampire and her henchman.

Stemming from this is perhaps the most spiritual theme in Vampyr: the concept of an afterlife and the destination of the soul based on one’s actions in this life. Perhaps Gunzburg’s determination to solve this crisis in a situation where he is really not needed illustrates an attempt to clear his own conscience and fix the dues for which he feels responsible. As Gunzburg wanders through this strange maze of mystery and fear, Dreyer challenges the viewer with extensive silence and a sense of genuine concern grows. Are Gunzburg’s thoughts debilitating enough to prevent him from overcoming this force? For Dreyer, faith is as lifesaving as it is challenging.

Day of Wrath (1943)

Despite challenging himself and audiences with his profound look at Joan of Arc’s faithfulness and the nature of evil in a quiet, normal setting, neither of these pictures was financially successful, which forced Dreyer to find work as a journalist while continuously searching for financial independence to realize his artistic visions. He succeeded in doing so by setting his sights on another play: Anne Pedersdotter, based on a 16th century Norwegian case of a woman unjustly accused of witchcraft. Here, the themes of spiritual suffering and moral responsibility are overt, but Dreyer goes further by exploring lust and how it clashes with deeply held beliefs and the strength of a community. Such ideas always seem prevalent in stories about puritanical religious communities, especially with regards to witch hunting. Nevertheless, Dreyer does not exploit the licentious or degrading elements of his characters and their circumstances. In this case lust and the allure of witchcraft is understood as a natural occurrence pushed beyond reasonable limitations by succumbing to the easily attained dark side of human nature.

This dark side of humanity has been interpreted by critics and audiences since the movie’s release as Dreyer’s commentary on the evolving political landscape of Europe in the early 1940s, especially his home country of Denmark’s occupation by the Nazis. Dreyer always denied this story being an allegory about the treatment of Jews but it is not so easily ignored. As the threat of evil grows, Absalon and his son must come to terms with their own relationship to this possible malevolence, personified by Lisbeth Movin as the seductive yet naive Anne. Like Falconetti in The Passion, Movin’s big, hypnotic eyes serve as a way to draw in the viewer, except here we must question the nature of her motives. Dreyer wisely keeps the fact of whether Anne is truly a practicing witch ambiguous, turning the audience’s attention to her relationships to Absalon, his son and his mother. Thus, this unique family plays out on the screen dark undercurrents within individual and familial relationships, and a clear-cut answer is not provided by the director.

Is Meret, the mother, right to so stringently accuse Anne of something based upon conjecture and association? Modern viewers might interpret this behavior as a mere consequence of unenlightened, irrational religious superstition foisted upon women in a repressive patriarchal society. Yet, Dreyer portrays Meret as perhaps the one true believer: a woman dedicated to pursuing the truth about this young woman and willing to sacrifice her son’s happiness and social status in order to expose possible dark forces in the village. Again, the idea of intolerance is raised but when it runs headlong into such strong convictions, the question becomes which of these concepts will prevail?

Within this cold, fascinating world resides the gorgeousness of Dreyer’s visual style: smooth angles, fluid camera movements and lighting capable of both hiding and exposing elements buried in the shadows. Of particular note here is Dreyer’s use of spatial layout and how the enormity of the chambers, hallways and outdoors seem to evoke both a sense of dread and peace. It becomes apparent that one of the main ideas demonstrated here is the possibility of evil emerging out of even the most unlikely circumstances, a theme carried over from Vampyr. Once this evil is confronted, Dreyer poses the idea that perhaps the true malevolence is betrayal and despair, as Anne is faced alone with her accusers. Could she have been saved if some were willing to stand with her? In any case, to stand for what one believes in appears to take greater courage than blindly accusing based on correlation. Even superstitious religious zealots recognize that.

Ordet (1955)

In English, Ordet translates to ‘the word,’ which in a religious context refers to the Christian depiction of Jesus Christ as ‘The Word,’ that is the human incarnation of God’s written laws and ethics. Yet within the Greek translation, another definition emerges from this context: Logos, used as a name for Christ (and the concept he embodies) but also describes the idea that the creation of the world resulted from both the Almighty Father (God) and his Son Jesus Christ, who is simultaneously one with the Father (part of the Holy Trinity) and His messenger sent to Earth for the purpose of redeeming humanity. Such a description merely for the title might imply that this is a deeply complex theological discussion with no entertainment value for the average moviegoer. Yet, Dreyer is able to present the possibility of understanding these very complicated and ancient ideas through the setting of another close-knit, agricultural village in the Danish countryside. Given his use of such a historical context in virtually all his work, it seems that he understood such settings to be where deeply held ideas are both born and challenged. After all, how strong is faith if it never faces opposition?

In the case of Ordet, this small community is split between two factions of the Danish Church: the main branch of Evangelical-Lutheranism and the Inner Mission sect, which still associates with the majority but disagrees sharply regarding the necessity of salvation to avoid hell. The story centers upon Morten Borgen, the patriarch of a prominent family of farmers, who has three sons: Mikkel, the faithless but devoted husband to believer Inger; Johannes, the theological student whose mental breakdown from studying Søren Kierkegaard has caused him to proclaim himself Jesus Christ, and Anders, who is dutiful to his family but also desires Anne, the daughter of Peter Peterson, the leader of the Inner Mission chapter. As a result of this difference, Peterson will not allow Anders to court his daughter, leading to a bitter feud between himself and Morten. It is within this storyline that Dreyer reveals his most obvious theme of spiritual conflict and its impact upon material conditions. Yet, perhaps because of their conflict they are understood by the audience and other characters to be less ‘insane’ and more mentally stable than Johannes, whose claims are interpreted as mere utterances of a lost mind. Is Dreyer calling into question our implication of this differential? Why should Johannes be seen as mentally ill when he is the only man willing to speak truthfully and graciously to everyone else?

Religious beliefs are a prominent component of all these villagers and in the case of the Borgen men, life has given them little incentive to hold on to these views. The faithful ones are those perhaps closer to the Earth in some sense: Inger, wife of Mikkel, mother to their daughters and close confidant of her father-in-law, who she tries to gently nudge towards faith; and Johannes, whose proselytizing and constant wandering about causes almost everyone else to treat him as a non-threatening but nevertheless absurd character they both pity and tolerate. Only Mikkel and Inger’s daughters, especially the eldest Maren, seem to appreciate the power of Johannes’ words and hold their belief in him despite the occurrence of real challenges to their circumstances. In these scenes, is Dreyer acknowledging the importance of child-like faith, an idea hearkening back to the words of Jesus who stated the impossibility of entering the Kingdom of God without such a state of mind? In an essay, writer Chris Fujiwara states that the few appearances of Johannes “shocks and alienates viewers” precisely because his speech and actions seem not to align with this world. Unlike the smooth, superficial and clinical feeling of the Borgen’s home and the village, Johannes is brazen in his desire to shake up the complacency of his family by warning them loudly and directly of troubles to come if they will not repent.

Unlike Vampyr and Day of Wrath, the threat to these characters comes not from outside the domestic setting but within: Morten, Mikkel and Anders all center their focus more on the realities of harvesting and maintaining domestic order than they do their individual spiritual journeys. As a result, they are left vulnerable when disaster strikes with only Johannes left to predict and interpret the impending difficulties. It soon becomes clear that the lack of disconnect between what Johannes says and what comes to pass illustrates tremendous spiritual potential in this home if the men are able to grasp their responsibilities and uphold the moral duties the women in their lives already adhere to.

Gertrud (1964)

For his final feature, Carl Theodor Dreyer pared down his unique style to its essence, culminating in a nearly two-hour movie composed of a mere 89 shots, unthinkable by nearly any subsequent standards. Yet, Dreyer’s clear-cut aesthetic allows the viewer to focus on the actors’ body language as well as the claustrophobic set design and costumes. So much of this world (early twentieth century Stockholm) seems to encroach upon the characters. Their movements are very compact; scenes between two people mainly consist of characters talking in one position, switching sides and resuming their conversation while the camera slowly moves around and back before leaning into what they are saying. In many ways, Dreyer’s visual style reminds the viewer of filmed theater, which many cinema fans see as anathema to the preferred aesthetic. Yet Dreyer persists in creating a slow, intense mood as the dialogue exchanges circle round and round, building the psychological intensity and spiritual crises.

A debate long held about Gertrud is whether or not Dreyer’s style is more reminiscent of cinema or theater. On the surface appears that by the end of his career, Dreyer had become disenchanted with elaborate camera moves and striking visuals. Yet, some reviewers such as Phillip Lopate state that “Gertrud is pure cinema: every frame is composed and lit exquisitely, balancing pools of lights and shadow; its small, gliding camera movements encircle the characters; it is anything but static, to those who enter its rhythm.” The question becomes who is willing to enter such an idiosyncratic rhythm?

The movie opens with melancholic piano music (a nocturne, we later learn) against rather austere-looking wallpaper for the credits before we move to the neatly adorned but seemingly lifeless office of government official Gustav Kanning and his wife Gertrud, a former opera singer. Almost absent-mindedly, they begin a conversation about their relationship, and it would seem Dreyer is challenging the viewer to remain interested. The actors hardly look at one another and their slight movements blend into the firmness of the surroundings. It’s almost as if the boredom of some viewers stems from what they bring to the picture, or is this Dreyer’s intent?

On the surface, Gertrud appears to be a divergence from his earlier work given the apparent lack of spiritual themes and an even slower pace and cynical mood than previously explored. Yet subtly Dreyer ties this final project back to his earlier works, particularly in the theme of deeply held convictions holding sway over other, more base desires. In the case of the former opera singer, she is so devoted to the notion of pure love (or love as a spiritual construct) that she is willing to sacrifice any and all other possible compromises in order to stay faithful to this ideal. Thus, her comfortable but loveless marriage to Gustav must go by the wayside; so too must a possible reconnection with her former lover, poet Gabriel Lidman, who apparently possesses the same unenviable qualities of her husband.

The only man we see Gertrud form any true passionate connection with is a young pianist, Erland Jansson; a man for whom she seems willing to cast aside all other elements of her life in order to attain this highest ideal of total commitment. In this way, Gertrud views love, especially in the context of marriage, as a spiritual goal that can only be gained if both parties are truly willing to make the necessary adjustments. In the case of Gustav and Gabriel she does not find what she needs but perhaps with this younger man? Is this a callous comment by Dreyer that we often look for what we want in the kind of people we secretly have other desires upon? Whatever the reason, Jansson is not willing to meet Gertrud where she wants since he apparently loves so much, he is in a committed relationship with another woman simultaneously. At this point, Nina Pens Rode conveys the complete complexity of emotions and thoughts of her character, but so quietly and without overacting that it also challenges the viewer to pay close attention. Like previous Dreyer actors, the smallest facial inflections can reveal a lot and with so many characters shut off from themselves and their objects of desire, the emotional turmoil of Gertrud rages inward.

What is one to take from such a story? Certainly it could be construed as a prettified disguise for what is essentially tawdry behavior and unlikable characters. Yet, one cannot shake the convincing nature of Dreyer’s style, which so elegantly and fragilely establishes a world where carnal emotions are mixed effortlessly with notions of the spirit. In the case of Gertrud, with love as her highest ideal, through her actions she forces the viewer to understand something typically thought of as a base human desire as something purer and loftier. For her, love is complete and total devotion and attention to the other partner; and given that her husband and ex-lover both pride their work above all they do not fit the mold. Yet, one cannot help but wonder if Gertrud is operating on a hypocritical level given her desire to make her relationship with Jansson work despite him placing his career and other women on the same level of importance. Does she willfully ignore this until it is no longer possible or is she making an exception?

In the end, Dreyer (like nearly all his protagonists), refuses to compromise his position or settle for a lesser view of what he believes to be of the highest importance. From the historical Joan of Arc to the more contemporary Swedish and Danish farmers and aristocrats, all these people hold tightly to their beliefs. And when they encounter difficulties the true test of faith emerges: how much do you truly believe what you say you do to the point of action? Similarly, it seems clear that Dreyer is not interested in characters who would say no to that question. Joan dies for her beliefs, as does Anne and Inger to a degree while Gertrud dies in a lonely manner. While the women stay firm to their principles, it is primarily the men in Dreyer’s work that must adapt their beliefs to reality, whether it be Gunzburg learning to believe in the evil of vampires or Mikkel coming to the realization that his wife’s and brother’s faith is legitimate. In Dreyer’s world, faith is the key to opening innumerable possibilities in life, some positive and others negative. But, of course, the important point is to stay the course, to not let others sway how you react and to keep the hierarchy of belief in mind. Only then can one attain a transcendent understanding of the principles needed to overcome and survive tribulation.

Leave a comment